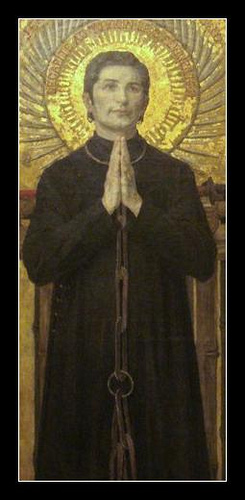

Letter from Theophane Venard

Letter from Theophane Venard

A Letter of St. Theophane

January 2, 1861

My dearest Father, Sister and Brothers,

I write to you at the beginning of this year, which will be my last on earth. I hope you got the little note which I wrote announcing my capture on the Feast of St. Andrew. God permitted me to be betrayed by a traitor, but I owe him no grudge. From that village I sent you a few lines of farewell before I had the criminal's chain fastened on my feet and neck.

I have kissed that chain, a true link which binds me to Jesus and Mary, and which I would not exchange for its weight in gold. The mandarin had the kindness to have a light one made for me, and treated me, during my stay in his prefecture, with every possible consideration. His brother came at least ten times and tried to persuade me to trample the Cross under foot. He did not want to see me die so young! When I left the prefecture to go on to the capital, an immense crowd came to witness my departure; in spite of the guards and the mandarins, one man, a young Christian, was not afraid to throw himself on his knees three times before my cage, imploring my blessing, and declaring me to be a messenger sent from Heaven. He was of course made prisoner.

After a couple of days I arrived at Kecho, the ancient capital of the kings of Tong-King. Can you fancy me sitting quietly in the center of my wooden cage, borne by eight soldiers, in the midst of an innumerable crowd of people, who almost barred the passage of the troops. I heard some of them saying, "What a pretty boy that European is!" "He is happy and bright, as if he were going to a feast!" "He doesn't look a bit afraid!" "Certainly he can't have done anything wrong!" "He came to our country to do us good and yet they will put him to death!" etc., etc. We entered the citadel by the eastern gate and I was brought at once before the tribunal of the judge of criminal cases. My catechist Khang, bearing his terrible yoke, walked behind my cage. I prayed God's Holy Spirit to strengthen us both and to speak by our mouths according to our Savior's promise; and I invoked the Queen of Martyrs and begged her to help her faithful child.

To begin with, the judge gave me a cup of tea, which I drank without ceremony in my cage. Then he commenced the usual interrogatory:

"Whence do you come?" "I am from the Great West, from the country of France."

"What have you come to do in Annam?" "I have come to preach the true religion to those who know it not."

"What is your age?" "Thirty-one." The judge here said aside, with an accent of pity, "Poor fellow! He is still very young!" Then he continued, "Who sent you here?" "Neither the king nor the mandarins of France; but I myself, of my own accord, came to preach the Gospel to the heathen, and my superiors in religion assigned Annam to me as my district."

"Do you know the bishop called, in the Vietnamese language, Lieow [Bishop Retord]?" "Yes, I know him."

"Why did he give letters of recommendation to the rebel chiefs to enroll the Christians?"

I ventured to ask the mandarin in reply, "From what source did you derive that information?"

"The prefect of Nam-Digne wrote us word of it."

"Well, then, I can bear witness that it is not true. The Bishop was too wise to commit so foolish an act, and if letters were produced to prove it, I should know that they were false. I saw the circular which Bishop Lieow addressed to his priests, in which he positively forbade their joining the rebel chiefs and declared that he would a thousand times sooner sacrifice his life than dip his crozier in blood."

"And the warriors of Europe, who took Touranne [Da Nang] and Saigon, who sent them? What was their object in making war on our country?"

"Mandarin, I heard the rumors of war; but having no communication with these European troops, I cannot answer your question."

At this part of the interrogatory the prefect arrived, and he had hardly taken his seat when he cried out to me, in a loud and angry voice, "Ah! You chief of the Christian religion, you have a clever countenance, you know very well that the Vietnamese laws forbid entrance into the kingdom to Europeans; what was the use, then, of coming here to be killed? It is you who have excited the Europeans to make war upon is, is it not? Speak the truth, or I will put you to the torture."

"Great mandarin, you ask me two questions. To the first I reply that I am sent as an ambassador from Heaven to preach the true religion to those who scorn it not, no matter in what kingdom, or in what place. We respect the authority of kings on the earth, but we respect more the authority of the King of Heaven. To your second question I answer that I never in any way invited or excited the Europeans to make war on the Vietnamese kingdom."

"In that case will you tell them to go? And you will then obtain your pardon."

"Great mandarin! I have no power and no authority in such matters, but if His Majesty sends me I will beg the European warriors to abstain from making war on the Vietnamese; and if I do not succeed, I will return here to suffer death."

"You do not fear death, then?"

"Great mandarin! I do not fear death. I have come here to preach the true religion. I am guilty of no crime which deserves death. But if the Annamites kill me, I shall shed my blood with great joy for them."

"Have you any spite or ill-will against the man who betrayed and took you prisoner?"

"None at all. The Christian religion forbids us to entertain anger, and teaches us to love those who hate us."

"Chief of the Christian religion! You must declare the names of all the places and people that have sheltered you up to this hour."

"Great mandarin! They call you the father and mother of this people. If I were to make such a declaration it would involve a large number of persons in untold misery. Judge for yourself whether it would become me to do this or not."

"Trample the Cross under foot, then, and you shall not be put to death."

"How! I have preached the religion of the Cross all my life until this day, and do you expect me to abjure it now?

I do not esteem so highly the pleasures of this life as to be willing to buy the preservation of it by apostasy."

"If death has such a charm in your eyes, why did you hide yourself when there was fear of your being taken?"

"Great mandarin! Our religion forbids us to presume on our strength, and to deliver ourselves to the persecutors. But Heaven having permitted my arrest, I have confidence in God that He will give me sufficient courage to suffer all torture and be constant unto death."

This is a summary of the questions asked me, and of my answers. The mandarins then proceeded to question my catechist [Pierre Khang] and inflicted ten strokes of the knout upon him. He bore them without flinching, God giving him strength all the while gloriously to confess the faith.

Since that day I have been placed in my cage at the door of the prefect's house, guarded by a company of Cochin-Chinese soldiers. A great many persons of rank have come to visit me and converse with me. They will have it that I am a doctor, an astronomer, a diviner, a prophet, from whom nothing is hid. Several visitors have begged me to tell their fortunes. Then they question me about Europe, about France, in fact, about the whole world.

This gives me an opportunity to enlighten them a little on points about which they are supremely ignorant, and on which they have sometimes the most comical ideas. I try above everything to slip in a little serious word now and then so as to teach them the way of salvation. But the Annamites are a frivolous race, and don't like serious subjects; still less will they treat on philosophy or religion. On the other hand, their heart is good, and they do their best to show me both interest and sympathy. My soldier guards have an affection for me, and though they have been blamed two or three times for letting me go out, they still open my cage from time to time, and allow me to take a little walk. Sometimes their conversation is not very proper, but I never let pass words of that sort; and I do not hesitate to speak to them strongly. I tell them that they lower themselves in the eyes of everyone by impure thoughts and libertine discourses; and that if they can talk in that way without blushing, they deserve nothing but pity, not to say contempt. My lessons make an impression. They are far more careful in their language now, and some have gone to the length of begging my pardon for having made use of indelicate expressions. Still I cannot say that everything is sweet and pleasant; although many are kind to me, some insult and mock me, and use rough language to me. May God forgive them!

I am now only waiting patiently for the day when God will allow me to offer Him the sacrifice of my blood. I do not regret leaving this world; my soul thirsts for the waters of eternal life. My exile is over. I touch the soil of my real country; earth vanishes, Heaven opens, I go to God. Adieu, dearest father, sister, brothers, do not mourn for me, do not weep for me, live the years that are yet left to you on earth in unity and love. Practice your religion; keep pure from all sin. We shall meet again in Heaven, and shall enjoy true happiness in the kingdom of God. Adieu. I should like to write to each one separately but I cannot, and you know my heart. It is three long, weary years since I have heard from you, and I know not who is taken or who is left. Adieu. The prisoner of Jesus Christ salutes you. In a very short time the sacrifice will be consummated. May God have you always in His holy keeping. Amen.